The Self-Loathing Client

Some clients present their badness or defectiveness as an essential part of identity. To them, self-loathing is not a symptom but a defining truth that is non-negotiable.

This usually rubs against tendencies of the therapist to be supportive, caring and inclined towards finding something to praise and encourage in the client. Often, such seemingly positive responses from the therapist are perceived by the client as mismatch and bad mirroring and they feel lonely, unmet and possibly angry. It is another proof of their often-unconscious assumption that no one can really see them or care.

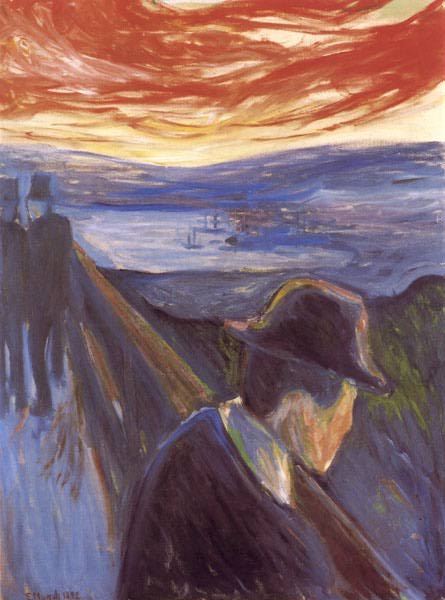

Self-loathing can present as a layer of cynicism, criticizing all ideas, situations and people. It can show up in bodily postures, habitual facial expressions and in a variety of self-harming behaviors. It can be expressed through rejection of any invitation or bid for connection. Even clothing can demonstrate a negative attitude towards the self. Beneath these presentations lie self-criticism, depression, and shame.

Generally, shame comes with secrets and hiding: “ I am defective and it is best that no one will find out about it.” The self-loathing person “chose” the strategy of advertising the shameful secret to not be surprised by others.

No one is born with self-loathing. According to object-relation theory, around age 2 the baby realizes that the mother/care-taker is not all good and the bad-mother splits from the good mother. Healthy development leads to re-integration of these through growing self-awareness, into a more mature understanding that both self and others are sometimes good and sometimes bad and there are ways for repair, correction and forgiveness.

The meeting with the internal object of the bad-mother can be too scary for some and in order to keep the inner mother image completely good, they make themselves bad. In some cases that is a life-saving move and the self-loathing person is stuck in that developmental phase, not seeing any alternative path.

A simpler developmental perspective suggests that children who grew up in a very critical environment—where every move was corrected, often severely—internalized the critical voice and might even experience it as some form of a protective adult presence.

A specific case of such a critical environment can be found in some very religious communities. In some religious traditions that emphasize original sin or innate sinfulness, children may be steeped in guilt and shame long before being introduced to the balancing themes of love and forgiveness. For sensitive children, this imbalance can be devastating and might end up being internalized a self-loathing.

Another developmental perspective suggests that children who experience abuse, could identify with the abuser and imitate their behavior. The core need is survival and safety. Since the abuser is the strong one, upon whom survival depends, it is better to side with them. Thus self-abuse is strangely perceived as a source of safety.

Toilet training can also be the origin of self-loathing. Parents who feel and express disgust towards the child’s normal digestive functions can imprint a sense of inadequacy and shame; even if the interaction is completely unconscious.

It is essential to remember that such developmental phases are mainly pre-verbal and are not subject to any reasoning. Trying to convince the client by pointing out the absurdity of their stance is futile.

At the same time, being open and receptive with the barbs, cynicism or bodily expression of self-loathing is painful.

The therapist needs to develop a fine control of their own shield, staying protected yet open; trying to demonstrate to the client the unconditional-positive-regard without mirroring back the negativity. As with all areas of therapy, the therapist has to continuously work on their self-awareness and inquire how they are impacted by the client’s self-loathing. Is there any unconscious shame and other negative attitudes triggered by the client’s expression?

Be aware of frustration or defensiveness in response to the client’s expression and ask “is it the client’s feeling or my feeling? Am I responding to the client here and now, or to some internal images from the far past?”

Only partly relevant is the image of Perseus’ shield that allows him to look indirectly at Medusa. The indirection protects him from turning into stone. Perseus is on a mission to cut off Medusa’s head, not a very therapeutic move. Similarly to Perseus, the therapist is trying to avoid turning into stone, but unlike Perseus, they try to reflect back to the client something positive, a long-forgotten memory of the good, protective and nourishing mother.

Looking sideways and through a reflection rather than directly, is usually a good choice, both metaphorically and literally.

A more resonating and useful image comes from Pullman’s trilogy His Dark Material. When the heroine Lyra goes to the land of the dead she meets the Harpies, half bird half human creatures that attack and kill any outsider.

Lyra tells the Harpies a true story — about her life and adventures in the world of the living. The Harpies are charmed. They have been living among shadows who never bring them anything real, only empty and endless repetition and they crave truth that they do not understand.

Lyra then offers a deal: the harpies will guide the ghosts of the dead safely to the exit, in exchange for hearing the true life-stories of those ghosts.

The harpies accept and transform their role — they become Witnesses of truth. Their leader even turns compassionate and saves Lyra from falling into the abyss.

Lyra does not mirror to the Harpies their evil side nor does she demand them to change. She appeals to their better side without any direct pressure.

That is something the therapist can attempt to reproduce. Faced with self-loathing and aware of the possible roots of it, the therapist can appeal to the hidden ‘good’ parts indirectly—through image and story—allowing the client to relate and respond as much as they can.

When the client declares their defectiveness there is no point opposing it. Even saying “I am sorry that you feel that way” can be experienced as bad mirroring.

Asking “which part of you says that?” might open a secret door, and it might lead to more opposition: “I am saying that! What do you mean by parts? I am not schizophrenic!”

In some cases it might work better to try to connect with the inner abused part; the one towards whom the anger is directed. After acknowledging the client’s anger and praising their courage to express it, one can try something like “it must be very painful to receive all this rage… I would feel very afraid if that was directed at me… I wonder how he feels…”

Eventually, on the way to healing, the client has to recognize and distinguish different inner voices. In Jungian language this is the separation that must precede integration. Healing would mean owning both good and bad sides yet placing the ‘self’ or any sense of identity more on the observing side.

In some cases, carefully chosen depending on the temperament of the clients and on the depth of the therapeutic relationship, the therapist can disclose how they feel when the client expresses self-loathing: “When you talk like this to Johnny, I feel very sad, almost despair.”

Even if the client objects, such phrasing models an inner separation between ‘you’ (the abusing critic,) ‘Johnny’ (the young abused part) and the observing self, modelled by the disclosing therapist.

Finally, it is essential to be very patient and go slowly. Getting early developmental stages unstuck is a slow process. Do not expect a gradual change but rather a long period of inertia that eventually reaches a tipping point. At the same time pay attention to tiny changes and when appropriate, point them out to the client and reframe them as success and progress. These can be a moment when the shield of cynicism was laid down or another expression of slight vulnerability.